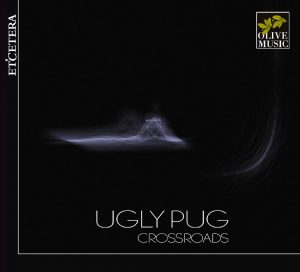

An essay written by Sara Constant for the liner notes of the CD booklet of Ugly Pug’s 2021 album Crossroads (Olive Music / Etcetera Records).

When Ugly Pug played at the 2017 Tampering Festival in Tampere, Finland, their all-premieres programme was billed as “new music for period instruments.” It’s a simple distillation of the Amsterdam-based ensemble, but an accurate one: a trio of recorder (Juho Myllylä), viola da gamba (Miron Andres), and harpsichord (at the time, André Lourenço; now, Wesley Shen), Ugly Pug has built its body of work on spinning a sound most commonly identified with the European Baroque into something new.

That all-premieres programme would become the backbone of what is now Ugly Pug’s first album. Crossroads features four works created in Tampere for the ensemble: Tero Lanu’s Introduction and Dance, Eetu Lehtonen’s Wormhole and Timo Kittilä’s Odds and Ends, plus two movements from American composer Carlo Diaz’s Reuse Music. The works are interspersed with sections from Wilma Pistorius’s eight-movement work Crossroads, commissioned in 2019. An arrangement by the ensemble of Polish composer Paweł Mykietyn’s 1991 piece La Strada closes the album.

If there is a lurking sense of anachronism to this album, it’s perhaps because of the way that these instruments have hopscotched through time and musical practice. Born in the Middle Ages, popularized during the Baroque, and revived in the 20th century through various early music and authentic performance movements, instruments like the harpsichord, recorder and viol are often seen as tools for recreating historically accurate Baroque-era sound. When players, composers, and instrument makers developed an increasing interest in using these instruments for newer works, the framing of that sound as a novelty—“old vs. new”—proved difficult to shake.

So what, then, is musical style in an album like this one? Is it something that people have, like a personality trait or a compositional ethos? Or is style something that we belong to, a space or time period we inhabit?

Those tensions are something the composers here seem to have recognized, and exploited. Crossroads and Odds and Ends both make use of many small movements (eight in the former, thirteen in the later) to poke briefly at different facets of the ensemble texture, and meld Ugly Pug’s vision of music-making with the composers’ own. Meanwhile, other works look to instrumentation to reveal subtle linkages between past and present. Introduction and Dance uses the deep, haunting sound of the Paetzold recorder—a huge plywood recorder first patented in 1975 by Joachim and Herbert Paetzold—to call back to something rhythmic and ancient. Wormhole does the same, blending Paetzold-heavy phrases reminiscent of Baroque music with uncanny electronic processing. Mykietyn’s La Strada, the only work not written for the Ugly Pug ensemble, is similarly dance-like, but with a mechanical lilt to it, and a relentless harpsichord backdrop that feels distinctly 20th-century.

Carlo Diaz’s Reuse Music is perhaps the most explicit in its coming-to-terms with history. Taking the score as artifact, it was created by filling in, piecing together and rearranging parts from Pietro Marchitelli’s twelve sonatas for two violins and harpsichord. The badly damaged manuscripts for these sonatas date back to 1700, and have not survived in full; here, the incomplete and often-illegible pages serve as Diaz’s starting point.

Miron Andres, Ugly Pug’s viol player, maintains that this kind of grappling with musical lineage is a core part of what it means to play a period instrument.

“When you play a certain instrument, it’s always connected with a certain repertoire,” he says. “Especially when you start playing early instruments like the viola da gamba.”

Miron first heard the sound of the viol when he was 13, on a recording of Frank Martin’s Cantate pour le Temps de Noël—a monumental work composed in 1930, which features among its string orchestra two solo viols. After that, he quickly took up the instrument, first pursuing studies in Baroque music.

He describes attending the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel, Switzerland—a city with a vibrant free improvisation scene, where his conservatory shared a campus with a general music conservatory that had a strong contemporary music focus.

“I really got to discover my own instrument there,” he says. “And then it kind of came to me at some point, and I started to think: what am I actually doing here? Is it really only ‘early music’?”

Thinking back to his first time hearing the viola da gamba, Miron describes how the instrument’s sound isn’t really comparable to any modern bowed string instruments. He was struck, he says, by the look of it, the natural playing posture. By the sound of its resonance, with more strings and different harmonics and overtones than any of its contemporary counterparts.

“An instrument with centuries of tradition, of playing practice,” he says. “But a sound that, despite its revival, most people have never heard before.”

—

As with Miron, the instrument Juho Myllylä plays in Ugly Pug was the first one he learned. He started learning the recorder at the age of six in Finland, eventually following his studies to Amsterdam—a city, like Basel, known both for its early and contemporary music scenes.

It was in 2014 at the Conservatory of Amsterdam where Juho met Miron, as well as André Lourenço, Ugly Pug’s founding harpsichordist.

“It was a particular piece that André and I wanted to play: the Finnish composer Jukka Tiensuu’s Musica Ambigua, from 1998,” Juho says. “It’s a cycle for period instruments, and in the last movement, you are free to play in any combination of these period instruments. And so first, it was recorder and harpsichord, André and I. At the time, Miron had already been in Utrecht for one year, and then he also came to the Conservatory of Amsterdam, to study one year of viola da gamba and then for a specialized master’s in contemporary gamba. So at this time, we had all arrived at the same school with this interest in contemporary music.”

Canadian pianist and harpsichordist Wesley Shen would eventually replace Lourenço, joining the group in 2018.

Wesley’s initial interest in harpsichord playing had been sparked by a contemporary work—a recording of György Ligeti’s 1968 solo harpsichord piece Continuum. He then worked up to it, first learning the early music repertoire as a way of getting to the new.

Historically, recorder, harpsichord, and viola da gamba formed a fairly standard ensemble, well-suited to the standard (though flexible) melody, bass and harmony roles of many Baroque chamber works. However, Wesley notes, from a modern perspective they have starkly different sound qualities.

“The harpsichord has an immediate, sharp attack and very little sustain,” he says, “while the recorder has a clear attack but it’s all very soft. And the gamba is sort of the opposite of all that: it’s a very slow attack, but then can sustain strongly, with much more control over the sound envelope.”

Thinking through the instruments in this way, it becomes clearer how the works that Ugly Pug plays on this album—though perhaps disparate in terms of style—share a common textural element, drawn from a modern, sound-based approach to the instruments themselves. It’s an approach grounded by its lack of loyalty to any one playing technique, historical practice or compositional school—one that takes its cues, sonic and otherwise, from the complicated and multifaceted present.

—

Sometimes, it feels as though bands like Ugly Pug are created to serve as a statement against everything we think we know. Even the group’s name (named after Sabba, the polarizing pet pug of Miron’s ex-partner) feels like a tongue-in-cheek jab at what we think of as standard ensemble practice: why name a new music ensemble in such a lighthearted way? But then again, why not? Why not detach ourselves from the institutionalized nature of this music, its seriousness, and seek out different ways of doing things?

Early music and new music are so often assumed to be opposites that many of our institutions rarely conceive of them as anything else. Perhaps the one thing that I have the sense the members of Ugly Pug are really confronting in this work is that entrenched, teleological view—that need to always define one musical space within the context of the other.

“The idea of ‘old vs. new’—it already categorizes the instruments, or the music, as a specific thing,” says Wesley. “It typecasts these instruments into specific roles, a specific feeling, a specific sound, instead of looking at their sonic qualities. It’s impossible to not have those connotations with the instruments or to negate their history…but a crossroads does imply that past and present meet at one point and never meet again. Maybe this crossroads is more like converging paths, somehow—different layers of divergence and convergence.”

Juho agrees.

“When we play early instruments today, it is filtered through our modern understanding of things. We can get close to tracing their history, but it’s always influenced by our modern ears,” he says.

“The earlier we go in history—the less we know.”